Endangering the media

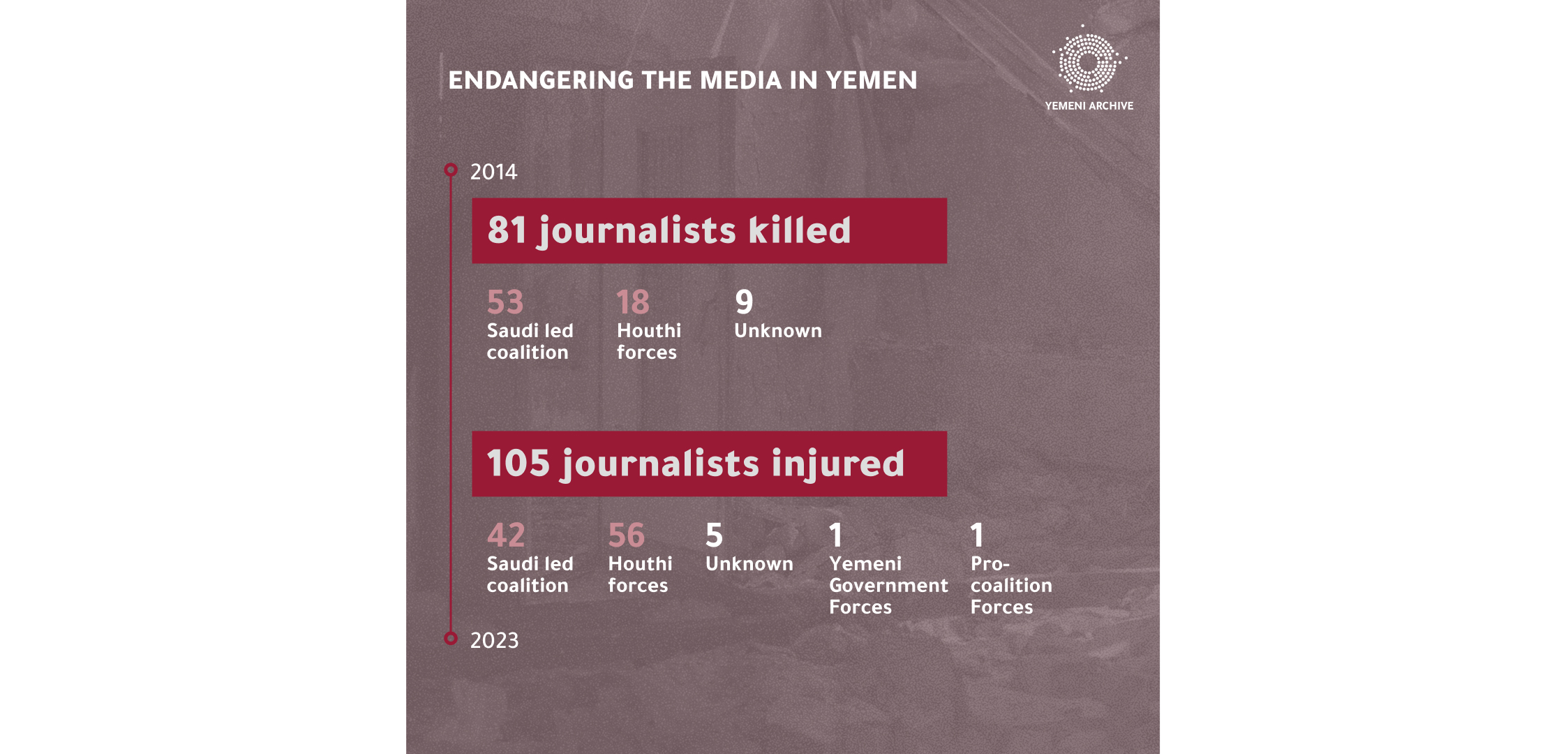

Yemeni Archive collected and archived all verifiable open source information documenting attacks impacting journalists and media in Yemen. Journalists and media infrastructure in Yemen have been attacked in at least 182 documented, armed conflict incidents since 2014. These documented attacks killed 81 journalists, injured 105, and damaged or destroyed 33 media houses or other key media infrastructure.

Armed attacks impacting journalists and media houses in Yemen have contributed to an overall shortage of information and data on casualties and destruction in what has become the world’s largest humanitarian crisis. It is with this dire need for information and under these extreme circumstances that journalists work in Yemen --- and are under attack from all sides of the conflict.

Here we present brief context and findings from our data:

BACKGROUND: Media in YemenWHO: Key actors in the attacks

WHAT: Key features of the attacks

WHERE: Locations of the attacks

WHEN: Timeline of attacks

WHY: Targeting the media as a strategy of armed conflict

BACKGROUND: Media in Yemen

Yemen has long had a troubled record on press freedom and independent media, but this has changed in important ways since the 2011 revolution and throughout the current conflict.

Since the start of the current conflict in September 2014, attacks on media in Yemen have increased. While Yemen’s troubled record on media freedom precedes the conflict, important changes sparked by the 2011 revolution, subsequent political transitions, the Houthi’s 2014 ascension to power, and the Saudi-led coalition’s 2015 intervention were all followed by notable deteriorations in the media’s ability to operate safely in the country.

Prior to 2011, press freedom in Yemen was tightly controlled with the Saleh government threatening and intimidating journalists into silence and self-censorship. Then, even as it allowed for more press freedom, the new, Hadi-led government in 2012 continued to intimidate and attack journalists—a decentralised, more open climate for media after the revolution meant journalists were more prone to attack from a greater number of actors.

Even before taking political and military control of Yemen’s capital Sana’a on 21 September 2014, the Houthi forces’ relationship with the media in Yemen has been an integral component of their strategy. Understanding this relationship is essential to a comprehensive understanding of the Houthi’s growing sources of political legitimacy and strength in the lead up to the current conflict. While it was mostly both local and domestic political and military factors that enabled the rise of the Houthis in 2014, their success was also supported by substantial, external media efforts that began in 2012 with the support of Hezbollah in Beirut. After the Saudi-led coalition launched its military intervention on 25 March 2015, the Houthis prioritised a takeover of state-controlled media outlets, leading to a situation in which most media in the capital and throughout northern Yemen became pro-Houthi. Yemen’s media ecosystem quickly became highly polarised.

And so, the media has been a key issue over which the Houthis and the Saudi-led coalition --- whose intervention in 2015 significantly exacerbated the already worsening situation for journalists --- have fought. The majority of Saudi-led coalition attacks on media includeded in this database occurred in Sana’a—the home of many of the state-run and independent outlets controlled by the Houthi forces.

On 14 September 2021, Kamel Jendoubi—Chair of the United Nations’ Group of Eminent International and Regional Experts on Yemen (GEE)—informed the United Nations Human Rights Council that “those perceived as dissenting from or opposing the party in control of territory, including human rights defenders and journalists…are particularly at risk.” In its most recent report, the GEE elaborated, “parties to the conflict have continued to violate the rights of journalists,” and specifically named violations to the “rights to life, liberty and security, freedom of expression, the right not to be subject to torture, including sexual violence, the right to work and fair trial guarantees.”

WHO: Key actors in the attacks

There are three key groups discussed in the data and findings report. Those impacted by the attacks: journalists and the organisations supporting Yemeni media infrastructure. The two armed groups allegedly behind the attacks: the Ansar Allah (Houthi) forces and the Saudi-led coalition (SLC) and affiliated forces. Lastly, for some cases, the groups behind the attacks on journalists or media infrastructure were not able to be determined and in the data and findings are left as unknown.

Journalists and media infrastructure in Yemen

Our data includes documented attacks against both journalists and media infrastructure. A journalist is “a person who attempts to obtain or comments on or uses information for the press or for radio or television; any correspondent, reporter, photographer, cameraman, or technical assistant, habitually carrying out such activities as his/her main occupation.” Our data does not include attacks against war correspondents. Media infrastructure includes physical structures used for and dedicated to supporting journalistic activities (e.g., media houses, television and radio broadcasting stations, and relevant equipment such as antennae).

Ansar Allah (Houthi) forces

Houthi forces took over the Yemeni capital of Sana’a in September 2014. As a rebel movement operating from northern Yemen, the Houthis have been in an on-and-off conflict with the Yemeni government since 2004. In 2010 they signed a ceasefire agreement with then-President Saleh’s government. But, one year later, the Houthis joined with other groups to oust Saleh. The following 2012 political transition known as the National Dialogue Conference (NDC) failed to satisfy the opposition. In its wake, the Houthis have gained a degree of political legitimacy damaging the government of Yemen as well as the government’s relationship with Saudi Arabia and the United States. The exploitation of perceived failures in the Saudi-backed NDC from 2012-2014 became the Houthi’s most significant political tool.

Our data indicates that between 2014 and 2023 Houthi forces have conducted at least 56 armed attacks impacting journalists and media infrastructure in Yemen. There are 18 journalist fatalities linked to these attacks.

The Saudi-led coalition (SLC) and affiliated forces

On 26 March 2015 --- and with the support of the United States and the United Kingdom --- Saudi Arabia led a military intervention into Yemen as part of a broader Arab coalition that included the United Arab Emirates (UAE)—and to a lesser extent—Bahrain, Qatar, Kuwait (until 2017), Sudan, Jordan, Morocco (until 2019), and Egypt. While the UAE announced the withdrawal of most of its troops in 2019, it nevertheless stated its intention to continue air operations in Yemen backing the increasingly powerful militias in southern Yemen, including the Southern Transitional Council (STC). Affiliated forces also include pro-SLC militias and the internationally recognized government of Yemen (GOY) of President Abd Rabo Mansour Hadi.

According to Yemen Data Project, as of March 2020 more than 18,400 civilians had been killed and injured by Saudi-led coalition airstrikes, which heavily impacted civilian infrastructure including water and transport infrastructure, hospitals, schools, and media infrastructure.

Our data indicates that between 2014 and 2023 the SLC and affiliated forces have conducted at least 79 attacks impacting journalists and media infrastructure in Yemen.

Among the 79 incidents in our data attributed to the SLC or SLC-affiliated forces, 53 were SLC airstrikes, 20 were by the internationally recognized government of Yemen (GOY), and another 6 attacks are attributed to other forces linked to the SLC. In total, these incidents resulted in 53 journalist deaths.

It is important to note that the official Yemeni government is internationally recognized and has received military support from the United States and other powerful democracies vis-à-vis the Saudi and Emirati coalition. And, altogether, the various actors that comprise the internationally-backed government of Yemen and the SLC, including those militias backed by the UAE, control territory inhabited by only 30% of Yemen’s population.

WHAT: Key features of the attacks

The incidents in this database are conflict-related armed attacks --- Yemeni Archive did not include incidents of arrest, kidnapping or abduction. For each attack included in the database, Yemeni Archive tracked the following notable features, all of which you can find in the public data. See the methodology page for more information on our research, including how we evaluated sources and our chosen standard of information when tagging the data for these key features.

Fatalities and injuries to journalists

In this data, journalists or other media personnel casualties are tracked in two categories of tags: whether any journalists impacted in the attack were killed and whether any journalists impacted in the attack were injured. If verifiable information points to yes, the tag is TRUE; if verifiable information points to no, the tag is FALSE. The default tag is UNKNOWN: if available information did not pass the chosen standard of information threshold for tagging, our researchers tagged “unknown.”

Repeated attacks

Repeated attacks are incidents impacting the same geographic coordinates, building structure, or structure grounds over time. If --- within Yemeni Archive’s own verified database of documented attacks --- there is more than one attack on this same set of coordinates, structure, or grounds under investigation, the data tag reads TRUE. If not, the tag is FALSE.

Direct hits

For each direct hit tagged in this database, the munition(s) or missile(s) used in the attack resulted in direct, physical impact on at least one category: the named journalist or the named media infrastructure. The default tag is UNKNOWN: if available information did not pass the chosen standard of information threshold for tagging, our researchers tagged “unknown.” For more information, see the section [WHY: Targeting the media as a strategy of armed conflict .]

| perpetrator | Media infrastructure sites | Number of attacks |

|---|---|---|

| Houthis forces and Saudi-led coalition | Attacks against Yemen Today TV | 3 |

| Saudi-led coalition | Attacks against media Compounds “YEMEN TV” | 5 |

| Saudi-led coalition | Attacks against Al-Marawaa Radio Station | 3 |

| Saudi-led coalition | Attacks against Jabal Aiban Radio Station | 3 |

Weapons used

Yemeni Archive tracked only general information, identifying weapons used for each incident from among these options: Airstrike, Artillery, Rocket Artillery, Rockets launchers, Mortar, Placed explosive, Landmine, Execution, Small arms, Unknown delivery method, and Unknown shrapnel. When evaluating the collected incident information, researchers gave greater weight to information provided as direct documentation --- specifically, eyewitness footage or footage of munition remnants that could be verified or otherwise authenticated and linked to the attack. The default tag is UNKNOWN: if available information did not pass the chosen standard of information threshold for tagging, our researchers tagged “unknown delivery method.” “Unknown shrapnel” was tagged, however, if Yemeni Archive identified a visual likely depicting munition remnants attributed to the attack but was unable to verify the exact munition or delivery method. “Execution” denotes an execution-style event for which small arms may have been used but that is nonetheless distinct from any other uses of small arms in conflict.

Area of control

Area of control research involved an evaluation of the geographic area surrounding the attack impact site on which faction of the conflict was effectively in control at the time of the incident in question. To determine this tag, Yemeni Archive searched historical data on frontlines from Liveuamap and corroborated this information with additional research. The tag options are: Yemeni government forces, Houthis rebel movement, Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), Pro-coalition forces, ISIS, Tribal militias, Disputed areas, and Unknown. For disputed areas the controlling group is contested or in flux, meaning multiple groups have a stake in control over the area and recognised or effective control changes both regularly and unpredictably.

Alleged perpetrator

Perpetrator attribution has been assigned to each incident for which a credible, reliable, and corroborated perpetrator allegation has been identified among the potentially responsible groups: the Houthi rebel movement, the Saudi-led coalition, Pro-coalition forces, Yemeni government forces, Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), and ISIS. All perpetrator claims were considered in combination with other information about the attack incident, particularly which group reportedly controlled the attack area (area of control), proximity to any frontlines, and weapons used or delivery method (for example, airstrikes were much more probably attributable to the SLC). The default for the alleged perpetrator tag was “unknown”: if available information did not pass the chosen standard of information threshold for tagging, our researchers tagged “unknown.”

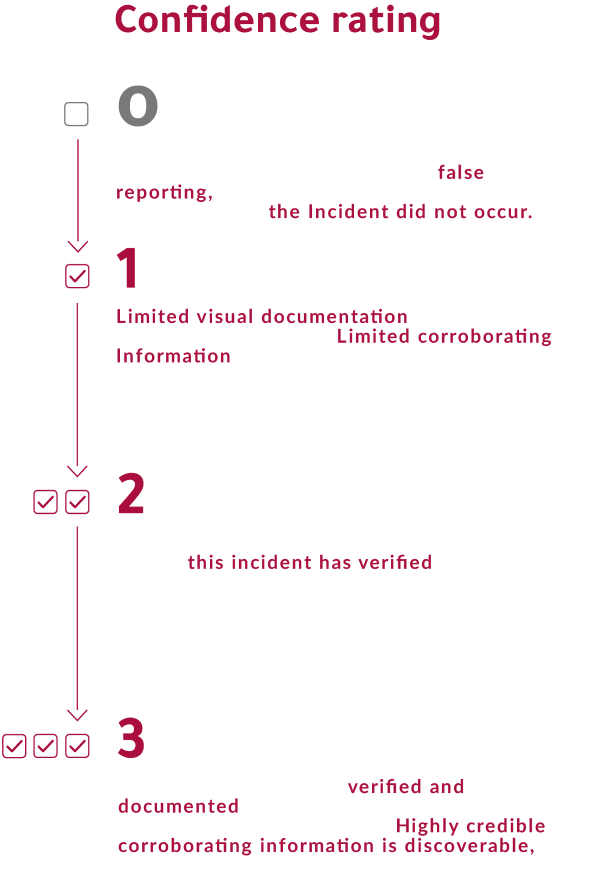

Confidence ratings

Each incident in the database has been assigned an overall confidence rating. This ratings system was created to give database users an evaluation of the discovered open source information for each incident as a whole. The ratings themselves are assigned based on the robustness and quality of information available for each given incident included in the database, relative to the other incidents that have been documented, archived, and included in this thematic database.

Specifically, confidence ratings are assigned as follows:

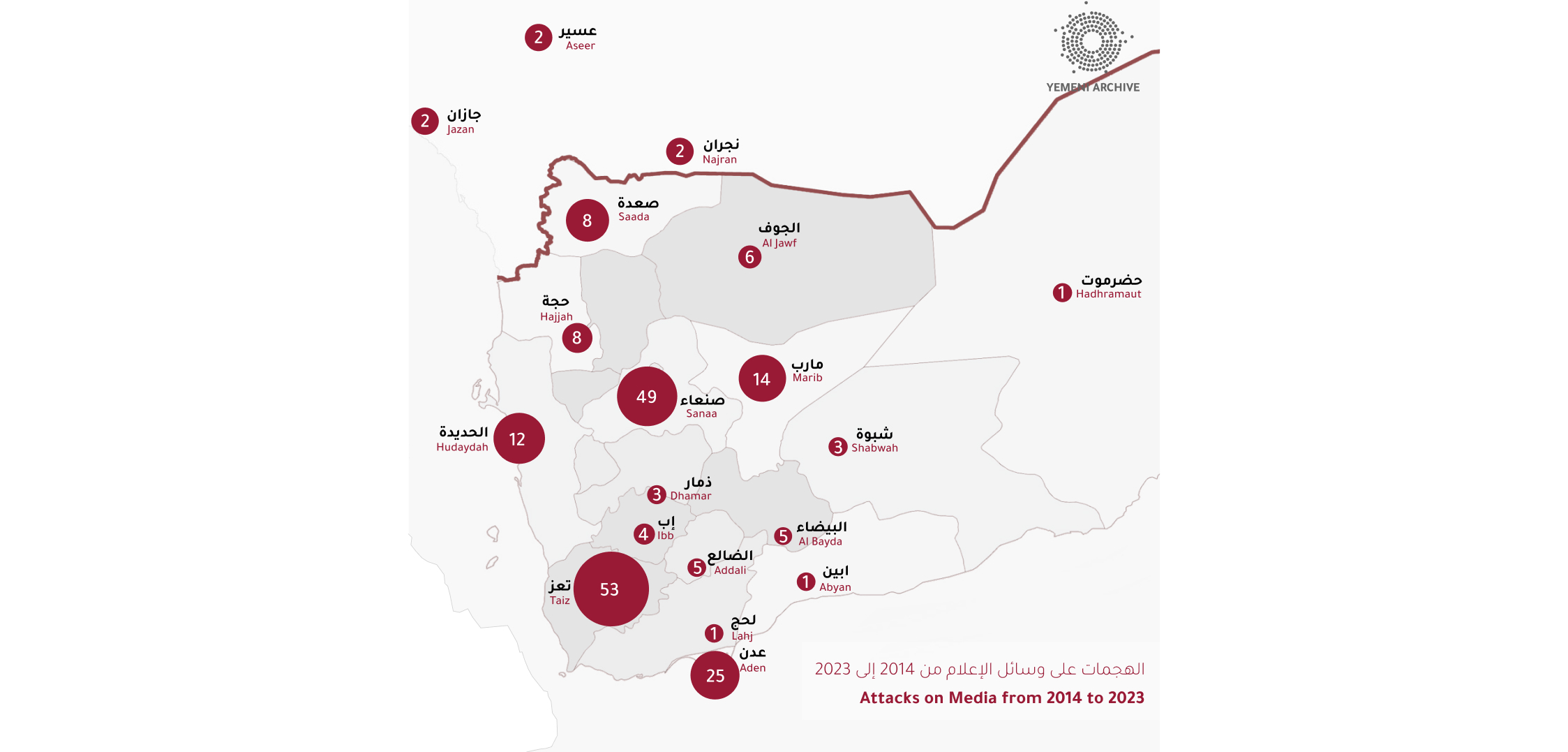

WHERE: Locations of the attacks

According to data collected by the Committee to Protect Journalists, for the last decade --- between 2011 and 2021 --- more journalists were killed in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) than in any other region. Available information on attacks against journalists and media in Yemen, however, has been even more limited than for other countries in conflict in the region.

Reviewing location information in our data, many of the documented attacks in Yemen occurred in areas holding strategic importance. This includes attacks on journalists and infrastructure in Sana’a, Yemen’s capital and most heavily populated city. Sana’a was the site of the start to the current conflict when the Houthis gained control over it in September 2014. As a cultural and commercial hub as well as one of the most contested cities in the conflict, Taiz is characterized by a high degree of political engagement and was central to the 2011 uprising against former President Ali Abdullah Saleh. Taiz reflects both the internal and externally-imposed political divisions that drive the current conflict in Yemen. Hudaydah and Marib are also central to the conflict for their positions as key commercial centers, with the Red Sea port in Hudaydah as the location for most imports and the city of Marib as the country’s main source of oil and gas. Notably, these latter 3 areas --- Taiz, Hudaydah, and Marib --- are regularly areas of disputed control among armed groups.

Among the documented attacks included in Yemeni Archive’s dataset, most of the attacks for which the SLC and SLC-affiliated forces are allegedly responsible were conducted in Sana’a, followed by Taiz and Hudaydah.

By comparison, most of the incidents included in the database for which Houthi forces are allegedly responsible were in Taiz—followed by Sana’a, Marib, and Aden—where there were an additional two unknown but suspected Houthi incidents.

WHEN: Timeline of attacks

The Yemeni Archive documented 182 attacks on journalists since the start of the conflict. Among these incidents, attacks most probably attributable to SLC were most frequent between 2015 and 2016 --- the first two years of the conflict. By comparison, the intensity of attacks in our database that are most probably attributable to the Houthis is relatively constant from 2015 until 2018, at which point the rate of attacks on journalists and media infrastructure decreases.

An observable decrease around 2018 and 2019 for these attacks may reflect three features of the conflict. First, certain types of attacks --- including imprisonment as a repression tactic --- are reportedly increasingly used but fall outside the scope and methods of Yemeni Archive’s database.

Second, the complexity and power of militias affiliated with the coalition have grown over time, relative to the SLC itself. The SLC has fragmented over time, and the UAE declared a withdrawal of its military forces in 2019. It is possible that this led to a further apparent decrease in documented attacks due to greater difficulty in tracking attacks by the increase in number and variety of these groups. Despite the 2019 Riyadh Agreement between the STC and pro-Hadi government, these divisions have continued to characterise fighting in southern Yemen in 2020.

Third, a ceasefire between the Houthis and the SLC in the southern port city of Hudaydah was brokered in Stockholm at the end of 2018. Insofar as patterns of attacks on journalists may be assumed to reflect broader patterns of fighting in the conflict, Yemeni Archive has preserved and verified documentation indicating more incidents of attacks on media in the governorate of Hudaydah in 2018 than any other year in that governorate, which is possibly indicative of a peak in fighting there prior to the ceasefire.

However, while Yemeni Archive data on deadly incidents attributed to the SLC shows a peak in 2015 and 2016, noteworthy attacks in high density residential areas continued on into 2018 JO_0048 and 2019 JO_0033. In 2018, an airstrike directly hit the filming site of a TV series killing Yemeni satellite TV producer and journalist Muhammad Nasser al-Washli and director of the decoration department Abdullah al-Najjar, among other reported casualties. In 2019, an airstrike hit the home of then-president of the Yemeni Media Union, Abdullah Ali Sabri. Sabri and his son Baligh were injured. Sabri’s mother (age 60) and two youngest sons, Loay (16) and Hassan (18), were among those killed in the attack.

The latest Yemeni Archive data indicates that between 2014 and 2023, 182 incidents occurred, including the killing of 81 journalists and the injury of 105 others.

WHY: Targeting the media as a strategy of armed conflict

The intent to target and attack the media is clear in these statements by representatives of the Houthi and SLC forces, both made early in the conflict. Trackable indicators of such targeting intent over time are, however, difficult to identify and analyse on a reliable and consistent basis across all incidents included in this database. This is especially true if seeking to examine intent behind attacks that impacted variably visually identifiable and mobile potential targets, journalists. Below is an analysis based on relevant international legal norms and identifiable trends in the data.

Journalists and media infrastructure are legally protected during armed conflict

Journalists and media infrastructure are both protected under the international laws of armed conflict as civilians and civilian objects, respectively. Journalists retain this protection provided “they take no action adversely affecting their status as civilians” (1977 Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions, Art. 79(2)), and media infrastructure similarly retain this protection provided they do not become legitimate “military objectives” (AP I, Art. 52(2)).

In Yemen, the Houthis and the SLC and affiliated forces have called media linked or sympathetic to opposing groups ‘propaganda.’ However, numerous sources—including the Committee Established to Review the NATO Bombing Campaign Against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia—have made it clear that disseminating propaganda does not itself render media infrastructure a military objective, because impact on civilian morale is neither a “military advantage” nor a “contribution to military action” (AP I, Art. 52(2)).

In certain circumstances — such as when it is used for military communications or to incite crimes — a piece of media infrastructure may constitute a military objective. But even then, an attacker must implement appropriate precautions against civilian harm (AP I, Art. 57(2)) and avoid causing incidental civilian harm that is disproportionate to the anticipated military advantage.

Parties to the conflict in Yemen nevertheless perpetrate and justify violence against the media.

Demonstrated in the statements above, as early as 2015 representatives for the main parties to the conflict in Yemen had already articulated an intent to target media they consider loyal to opposing groups. Since then, some of these parties’ behaviors continue to signal their intent to target Yemeni media.

First, Yemeni Archive has found in our database attacks against journalists who were indeed embedded in and working for Houthi media outlets (see, e.g., JO_0043, JO_0030, JO_0031, JO_0041, JO_0056, JO_0080. It is possible they were therefore caught up in the militarisation of the media on both sides, namely a proliferation of Houthi propaganda on the one hand and, on the other, the publicly acknowledged SLC policy of intentionally targeting any media it deemed affiliated with the Houthis. Regardless, intentional attacks against even embedded journalists contributing to propaganda are unlawful.

Second, attacks against media infrastructure and personnel documented here have also affected independent — i.e., wholly unaffiliated — journalists and those critical of various sides to the conflict. This dynamic is reflected in instances of infighting among coalition members, which began in 2017. In November 2017 JO_0028, for example, UAE-backed forces allegedly attacked a radio mast of pro-SLC, pro-Hadi government news outlet Watani FM in Taiz. A journalist and witness to the attack stated, “The site is close to a military site, but it is known that the broadcast building or broadcast tower is a civilian site…We demanded an investigation but unfortunately, till today, no one bothered to communicate with us, to inform us about anything, or even to apologize to us.”

Third, despite public outcry against and official requests to investigate what is widely considered to be systematic, targeted attacks against journalists and media infrastructure in Yemen, there has been no official response. In 2016 the SLC established “the Joint Incidents Assessment Team” JIAT, an investigative mechanism into “claims and accidents” during coalition operations in Yemen. However, the mechanism has fallen short of international standards, “doing little more than covering up war crimes” according to Human Rights Watch.

Occasionally, however, attackers change narrative, seemingly in recognition of journalists’ and media infrastructure’s protected statuses as civilians and civilian objects. One notable example of the coalition admitting to “wrongful target[ing]” after initial denial was the October 2016 airstrike on a funeral hall JO_0042, which killed scores of civilians and injured many others including 9 media workers.

Identifying targeted attacks against media infrastructure

Yemeni Archive has tracked for each incident circumstantial indicators of a deliberately targeted attack. We divide this analysis by potential target type: relatively immobile media infrastructure and mobile, variably identifiable journalists.

At least 33 of the 182 documented attacks in our data impacted media infrastructure. These are: 12 attacks on television news agencies, 15 on radio facilities, 4 on a local newspaper office, 1 on a press car, and 1 on a Ministry of Information building. Of these 33 attacks on media infrastructure, 8 resulted in casualties.

The following indicators should be considered together with the full facts of the incident. Contextualised, each indicator may reflect different dimensions of intentionality as it is broadly understood. For instance, we have attempted to identify the information most useful as indicators of precise, targeting intent to attack a civilian object ― a media structure. However, and depending on the facts of the attack, they may instead point to intent to impact civilian infrastructure more generally, such as by indiscriminate bombing. We provide them here as a tool for organising our collected data, and leave decisions on how to use and interpret this information to the reader.

For attacks impacting media infrastructure, circumstantial indicators to help identify targeted attacks include:

- Location of the attack, especially its proximity to disputed areas, frontlines or potentially legitimate military target(s);

- Whether characteristics of a targeted attack can be identified, or whether the attack was conducted in such a way that indicates targeting;

- Whether there have been repeated attacks on same structure over time; and

- Weapons used, evaluated for precision and targeting capabilities.

Nearness of the documented attack to active fighting ― proximity to frontline or attacks in areas of disputed control ― and nearness to potentially legitimate military targets should be considered when evaluating for intent to target specific structures with an attack. A structure situated along a frontline or next to a military objective may be both impacted in the attack and not deliberately targeted, so long as it falls within a reasonable margin of error and assuming no egregious errors have occurred. Attacks outside of disputed areas as well as greater distances from frontlines and military objectives may circumstantially indicate relatively higher potential that the perpetrator intended to target a particular, impacted structure.

Given the limited public information available on and complicated legal analysis behind assigning legitimate military objectives, Yemeni Archive has tagged this dataset with area of control and proximity to frontlines information only. And, in our data, proximity to frontlines are measured only in relation to officially recognised, settled frontlines, such as the front lines in south of Hudaydah city where the areas of Al Rabsa and the airport have been areas of dispute between the parties to the conflict. The distance between the geolocated attack coordinates and the nearest frontline is mapped and measured using Google Earth’s ruler tool. These are distinct from informal and fluctuating disputed areas. Of the 25 documented attacks impacting media infrastructure in our data, none were located directly on a settled frontline, the closest Faj Attan incidents estimated at over 2 kilometers from the frontline at the time of attack. Of the 25 attacks against media infrastructure included in our data, none of them took place in areas of disputed control.

Yemeni Archive has also defined certain, observable characteristics of armed attacks impacting immovable, physical structures --- such as media houses or other civilian objects --- that constitute circumstantial indicators that an attacker may have intended to target those structures. For this database, we tagged for verified direct hits. In the Yemeni context, direct hits on physical structures is particularly meaningful information to track. In this conflict, widespread, indiscriminate bombing and area bombardments are relatively infrequent. As compared with other contexts where such indiscriminate bombing is a more common occurrence, a verified direct hit in Yemen might therefore be a relatively stronger indicator of the attacker’s intent to target the impacted structure. Of the 25 attacks against media infrastructure included in our data, for 21 the perpetrator directly hit it, signifying an intent to target that structure.

If conducted by the same perpetrator or perpetrator group, repeated attack incidents impacting the same geographic coordinates, building structure, or structure grounds over time indicate a targeting intent behind the subsequent attacks. Four media infrastructure sites included in this database were attacked more than once, with a total of 14 repeated attacks by the same perpetrator.

For 1 of the 2 SLC airstrikes that impacted Yemen Today TV (JO_0023), the Saudi Ministry of Defense referred to the Faj Atan bombing on 20 April 2015 as one against a weapons depot and therefore a legitimate military objective. Notably, such a description fails to mention the Yemen Today TV station that was also hit or the civilians killed in the attack, including journalist Muhammad Shamsan. And this same TV station was hit once more by an SLC airstrike (JO_0016) - in addition to 1 attack attributed to the Houthis (JO_0090). The Houthi attack on the pro-Houthi/Saleh Yemen Today was on 2 December 2017, the same day that former President Saleh announced his intention to begin working with the SLC in fighting the Houthis.

Another 5 SLC airstrikes impacted a different television station in Sanaa, Yemen TV. All 5 were direct hits. The first two (see: JO_0027 and JO_0015 were in May 2015. At the time of the third airstrike on this building in September 2015 JO_0017, there were claims on social media that Yemen TV had kept weapons inside of its building. After investigating these claims, Yemeni Archive found that there was a direct hit on the Yemen TV building and on the military base next to it, Camp 48 under Brigade 4. Claims may have conflated the visuals from two attacked locations: available documentation indicates the latter was indeed used for weapons storage. The SLC directly hit Yemen TV yet again on 8 December 2017 JO_0021 and 22 January 2018 JO_0022. Yemeni Archive did not find similar claims of weapons storage or other possible military use of the Yemen TV building for these two subsequent attacks.

The remaining repeated attack figures include: 3 SLC airstrikes all direct hits on Jabal Aiban Radio Station (see: JO_0004, JO_0011, and JO_0019) and another 3 SLC direct hit airstrikes on Al-Marawaa Radio Station (see: JO_0010, JO_0013, and JO_0052). Repeated attacks can also provide the Houthis with another useful opportunity to highlight the SLC’s airstrikes on civilian targets, as part of anti-SLC propaganda. Similarly, the Houthi’s own attacks on media infrastructure, such as the one on 2 December 2017 on Yemen Today, can be used by the SLC to remove attention from its own role in attacking that media building and others. SLC attacks on media stations are called examples of ‘Saudi aggression’ by Houthi sympathizers and supporters, language the Houthis have used since the start of the SLC intervention when describing military action by the SLC. Likewise, SLC-affiliated media outlets have been quick to cover attacks on media by the Houthis, accurately describing the 2017 Houthi attack on Yemen Today, but without mentioning that the SLC had itself bombed it in 2015.

Weapons used can also be indicative of an attacker’s possible targeting intent insofar as without more information a weapon with precise targeting capability can reasonably be assumed to have actually hit the attacker’s intended target. For the 33 total attacks in our data impacting media infrastructure, 21 are airstrikes attributed to the SLC, 5 were small arms or ground-to-ground attacks attributed to the Houthis, and 1 was a small arms attack attributed to Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). Given limitations on types and specificity of information available to Yemeni Archive in our investigations at this time, we were unable to collect sufficiently detailed information about weapons used in these incidents to analyse precise targeting capabilities. Generally, however, the attacks on media infrastructure appear to show the SLC using airstrikes to target media buildings affiliated with pro-Houthi positions --- all 21 SLC attacks on media infrastructure were airstrikes --- and Houthi forces predominantly relying upon small arms and ground-to-ground attacks. For a majority of these Houthi attacks, weapons information and affected individual journalists could be verified but not the buildings.

On 14 May 2019, the Houthis claimed responsibility for drone attacks on Saudi Aramco oil facilities. In response, the SLC announced the launch of a military operation to neutralize the military capabilities of the Houthi forces, stating their intent to target Houthi sites and weapons depots.

Two days later on 16 May 2019, SLC airstrikes hit 2 media-affiliated locations in Sana’a: the first hit the large, multi-family residential building JO_0039 in which Abdullah Ali Sabri, then-president of the Yemeni Media Union and his family lived, and the second hit the Ministry of Information building JO_0039 which organizes the work of journalists and media, including the Yemeni Media Union.

Yemeni Archive has anaylsed eyewitness videos to verify the timing and locations of the May 2019 airstrikes. The Ministry of Information building and the building in which the Sabri family lived were located approximately 3.9 kilometers apart in different areas of the city. They were hit close to the same time: 08:16am for the residential building and 08:32am for the Ministry of Information. Eyewitnesses report only one plane in the sky at the approximate time of these two attacks, though we cannot corroborate this claim. It is possible, given these reports and the very close timing, that both locations were damaged in attacks carried out by the same plane.

Looking to aftermath footage showing the scene of the residential building airstrike, this building was clearly directly hit and at the center of the area of destruction.

Sabri’s family are among the documented casualties of this attack: Sabri and his son Baligh were injured, and Sabri’s mother (age 60) and two youngest sons, Loay (16) and Hassan (18), were among those killed. From the information available to us, Yemeni Archive is unable to find any indication that this building was used for any purpose aside from civilian homes. A representative for the SLC later issued a public acknowledgement that there may have been accidental loss of civilian life resulting from its 16 May 2019 attacks on Sana’a, which was referred to the JIAT. The JIAT has not yet issued the results of its investigation into this matter.

Identifying targeted attacks against journalists and other media personnel

At least 118 of the 182 documented attacks in our data resulted in casualties to journalists or other media personnel.

Some of these 118 incidents overlap with the 33 counted in attacks impacting media infrastructure in the previous section, as attacks impacting media infrastructure can and do also harm the journalists and other media personnel working there. For example, the SLC airstrike that destroyed part of the Yemen Today TV building on 20 April 2015 JO_0023 killed journalist Muhammad Shamsan. The Houthi missile attack on the same Yemen Today TV building on 2 December 2017 JO_0090 injured four journalists.

There are also 3 incidents in which journalists’ homes were hit in attacks. For 2 of these, airstrikes attributed to the SLC resulted in casualties among journalists and among their family members (see: JO_0001 and JO_0033). For the third JO_0040, pro-SLC forces reportedly planted explosives in the home of two journalists, though this did not result in death or injury to the journalists.

Like for attacks linkable to physical structures, circumstantial indicators of intentional, targeted attacks on journalists are similarly possible to identify, but even more challenging to consistently and dependably track on a database-wide scale. Given journalists and other media workers are mobile, dynamic, and variably identifiable as members of the press, targeting indicators necessarily differ from those listed above for media infrastructure. Again, these indicators should be closely analysed with the full facts of the incident. Contextualised, each indicator may ultimately reflect different dimensions of intentionality as it is broadly understood.

For attacks impacting journalists and other media personnel, circumstantial indicators to help identify targeted attacks include:

- Location of the attack, especially its proximity to disputed areas, frontlines or potentially legitimate military target(s);

- Location of the journalist, relative to active fighting;

- Identifiability of the journalist as media or civilian at the time of the attack; and Weapons used, evaluated for precision and targeting capabilities.

Examining the incidents included in our database on a case-by-case basis, relevant examples and data points emerge. Consider the following examples.

In a July 2018 JO_0047 SLC airstrike on a disputed area in Saadah, it was not possible to ascertain what the intended target was. A witness told the Yemeni Archive team: “During this bombing, only me and the photographer were present in that area, as we went to take some general footage of the Directorate of this place. The place is 100% populated with civilians. We climbed on the roofs of the houses and then moved to a hill next to one of the houses in the middle of the farms, a populated civilian area, which was inhabited before the aggression, but with the continued bombing the people were forced to flee.” Even though they were working in a disputed area, such circumstances and surroundings to the site of an airstrike are circumstantially indicative of a perpetrator having the intention to attack civilians —which journalists are— and civilian objects.

In multiple incidents included in our data, ‘frontline’ journalists in Yemen reportedly took such steps to try to ensure they were not caught in the crossfire. These measures may be insufficient if journalists are nevertheless being deliberately targeted. In Taiz in August 2015 JO_0051, an al-Masirah cameraman Abdullah Ahmad al-Kabsi was killed allegedly by SLC snipers while working in a disputed area in which no active fighting was taking place while covering civilian displacement and airstrikes that had hit civilian houses. According to his brother, “he was sniped by one of the mercenaries’ snipers in the palace area from one of the houses, that is, it was not in a military area or a clashes area but from a house.”

Reflective of the significance of weapons used in an attack, Yemeni Archive data shows that as compared to the SLC and SLC-affiliated forces, Houthi forces used small arms more frequently in the attacks, as well as mortar, rocket, and —in two cases— conducted public executions of journalists (see:JO_0123 and JO_0101. The SLC’s use of larger impact airstrikes, by comparison, makes for a more difficult analysis of whether individuals were specifically targeted, were merely caught up in military crossfire, or were killed on a blurred boundary between the frontline and civilian areas (see, e.g., JO_0047.

In February 2016 JO_0096, journalist Ahed al-Shaibani was killed on the frontline in Taiz by small arms, likely sniper fire. A witness to the killing told Yemeni Archive it was clear al-Shaibani was a journalist as he had his press badge and press bag: “Ahmed was wearing his press bag and his bag was clear, and if you saw the pictures, you would have seen that Ahmed was defenseless, and militias that could hit him in the head could have recognized him as a journalist carrying and wearing his press bag.” The reported combination of sniping and press identifiers indicate a likely targeting intention behind this attack.

Yemeni journalists share how it feels to be targeted for their work

Yemeni Archive’s database does not and cannot fully communicate the experience of living and working as a journalist in a conflict zone where parties to the conflict have publicly stated their intent to target members of the press. Each documented attack has had traumatising, lasting impacts on Yemeni journalists and their families.

While speaking to journalists in Yemen and witnesses of attacks against journalists, Yemeni Archive researchers were pointed to the public statements by Houthi and SLC representatives, and repeatedly told variations on this prevailing sentiment: “The deliberate targeting of media professionals is at the forefront of the conflicting parties. Media people are a big target” (statement by a witness to a June 2017 attacks JO_0131 that injured photographer Fawaz al-Wafi).

A journalist who asked to remain anonymous said: “Us journalists always face heavy gunfire wherever we are covering a battle...I have covered several fierce battles and in those where there is press present, the Houthis always intensify their shootings towards us.” He fled Yemen under constant threats to his life and safety.

A friend of Muhammad al-Absi (JO_0101) shared that in the time leading up to his poisoning, ”[Muhammad] would not go out in the car for fear that they would plant an explosive device in it.”

Abdullah Ali Sabri, the former president of the Yemeni Media Union, lost his mother and two youngest sons when an airstrike hit his home JO_0039. Sabri’s surviving son, Baligh, described the attack’s aftermath: ❝I woke up as if I was in a nightmare…I was in shock when I saw my father screaming from pain, as his leg was broken and bleeding out. On the other side, I saw my brother lying on the ground and wasn’t moving, as he was between life and death. I did not know who to help first, my father, my brother or my grandmother.❝

These testimonials describe only a fraction of what Yemeni journalists face every day while documenting and reporting on the world’s ”forgotten conflict.” And, so long as journalists in Yemen are unable to work freely and safely, information available to members of the international community seeking to hold powerful stakeholders and perpetrators to account will continue to be extremely and unacceptably limited.